|

|

|

|

|||||

Session:New Developments and New Urbanism (March 12, 2:30pm)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Problems in Implementing New Urbanism

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Session:New Developments and New Urbanism (March 12, 2:30pm) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Abstract: The experience of Windsor, Ontario in implementing a large scale New Urbanist development plan for the East Riverside community suggests that commitment and consensus are key elements in the successful realization of the planning goals. Because the necessary support was weak or lacking in the Windsor case, a number of key elements of the original plan were compromised. In particular, the lack of alleys, front garages and the absence of coordination in the timing of developments have significantly altered the community’s appearance. Although the resulting development has been well received in the market, it is more contemporary than Neo-Traditional.

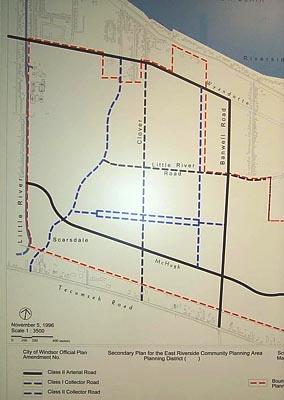

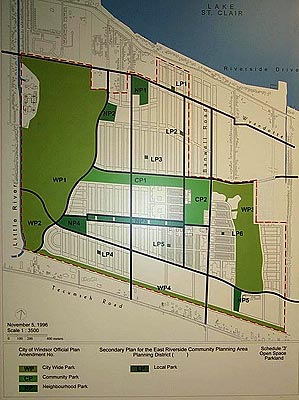

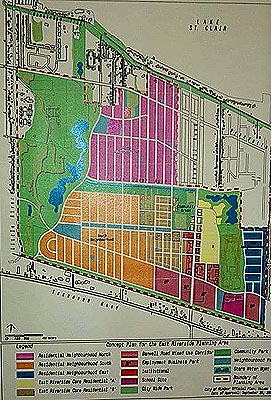

INTRODUCTIONPlanners throughout North America have long recognized the importance of implementing the plans that have been developed. No matter how elegant a plan is theoretically or conceptually, no matter how attractive the brochure or slick the presentation, plans will ultimately be of little value if they cannot be turned into bricks and mortar reality. In practice, this requires that planners have the ability to convince a broad array of stakeholders that the proposed plans will have "better" results than the other available options. This criterion for successful planning applies equally as well to New Urbanist planning schemes — they are better only if they can be successfully implemented. The New Urban News (October/November 2000) has identified more than 300 New Urbanist developments across North America, most still in the planning or early development stage. (In 48 of 306 U. S. projects, construction has reached at least 30 percent; only five projects are listed as complete.) The relatively small number of projects that have progressed into their implementation phase have generally been successful. In addition, a much larger number of developments have begun to adopt the New Urbanist label, often for developments that lack many of the essential attributes of Neo-Traditional canons. This paper presents a case study of a large-scale development that was planned along New Urbanist principles that has progressed to the implementation stage. While not yet complete, the East Riverside Community plan in Windsor Ontario is sufficiently far along that some indication can be gained of the lessons that can be learned. BACKGROUNDWindsor, Ontario is located directly south of Detroit, Michigan. With a population of more than 200,000, Windsor is the automobile capital of Canada. With a number of vehicle assembly and parts plants, Windsor is a manufacturing center for the Big Three auto companies, headquarters of Chrysler Canada and numerous auto parts supplier firms. The local economy is closely tied to the fortunes of the auto industry, with the attendant steep economic cycles. Over the long run, and particularly during the past decade, the local durable goods industries have supported a generally high standard of living in this metropolitan area. The East Riverside Community Planning Area is located at the eastern limits of the city of Windsor. The 1,165 acre site has well defined boundaries: Lake St. Clair to the north, the Canadian National Rail road line to the south, public parklands to the west and the Town of Tecumseh to the East. The land was mostly vacant. In 1994, CN Real Estate owned most of the land. (Other property owners included the City of Windsor, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and several small private landowners.) CN hired a Toronto planning consultant in 1994 to develop a plan for the development of this property as a mixed-use development following New Urbanist principles. In the course of developing the plan, there were numerous agency consultations. Design Charettes involving the general public as well as institutional stakeholders were held. In 1995, however, CN abandoned its land development activities and sold the property in several large parcels to local interests. The major new property owner continued the planning process, using the same planning consultant and the same concept. Other new property owners remained uninvolved. Public meetings introduced the development plan in 1996, to generally positive audiences. DEVELOPMENT PLANThe Development Plan that was adopted in 1998 included the following elements (Figures 1 and 2):

The Plan called for the major streets in East Riverside to connect to the city arterial street system, although no major access would be permitted to the scenic drive along the lakeshore to the north (Figure 3). Local streets would be developed in a grid pattern, with all residents within a five to ten minute walk of major streets and public transit. Parklands consisting of Regional (230 acres), Community (40 acres) and Neighborhood (30 acres) facilities would provide an important structural element for the community (Figure 4). With some modifications made in response to objections from adjacent property owners, the consultant’s Plan was adopted by the Windsor City Council as the Official Plan for the East Riverside Community in 1998. Implementation ToolsIn Ontario, Community Plans, such as the one for East Riverside, provide the general framework for development of an area. The implementation of these Community Plans is accomplished through both legislative and administrative processes. More detailed Plans of Subdivision and Zoning Bylaws are officially adopted by the local legislative body (City Council). Some aspects of the implementation are subject to a Design Approval process also requiring administrative approval. Subdivision Plans. The implementation of the Plan for the East Riverside community required the review and approval of a series of subdivision plans that established the overall framework for the community. The considerable interest generated by the planning process contributed to the rapid submission of several subdivisions in the Core and Neighborhood areas. The subdivision plans created the basic layout of blocks (Figure 5). They did not define the individual building lots, however, to allow for flexibility in the development of the neighborhoods. The subdivision plans provided the grid street pattern called for in the Community Plan. Although the street pattern is similar to what exists in the older parts of the city there are few connections between the new development and the rest of the city, in part because of neighbors’ objections. Boulevarded entrances are intended to provide a sense of identity for the community. Sidewalks are integrated with the curbs on both sides of many of the streets. Along with unique street lighting fixtures, the sidewalks also help to set the East Riverside Community apart from the other suburban developments. A bikeway right-of-way parallels the major road leading to the commercial core. The major parklands that occupy 25 percent of the land area) provide additional linkages in all directions. Zoning Regulations. Several new zoning districts were created for the East Riverside Community. These zoning regulations are summarized in Figures 6 and 7. In general, these zoning categories were intended to implement the design concepts expressed in the Community Plan. These regulations are often more prescriptive than the standard zoning bylaw, especially in the Core Commercial and Residential areas (see also Figure 8). For example, in the Core Residential areas, both minimum and maximum lot frontages are generally prescribed, rather than only minimums, to ensure that overall density will fall within the desired ranges. In some districts, minimum height restrictions and minimum floor areas are also established. At the same time, the regulations allowed for residential units to be included on the upper floors of neighborhood commercial developments, one of the few areas of the city where this is allowed. City policy prevented the inclusion of lanes (alleys) in this development. While this meant that the garages were accessed from the front (and often placed at the front of the house), the zoning limited the extent to which the garage could extend beyond the front building line of the primary structure. Design Review. For apartments, commercial and business park developments within the East Riverside Community, new developments are subject to a design review process. Administrative approval is required for these site plans. Thus far, no major developments subject to design review have been proposed. Obstacles And ConcernsThe East Riverside Community plan, as envisioned by the consultants and the original landowner (CN), called for the development of one of the largest New Urbanist projects in Canada. The realization of this planning concept, however, has encountered a number of practical obstacles. As a result of both contextual and procedural factors, there are considerable differences between the East Riverside community plan and what has been developed on the ground. In retrospect, there are a number of reasons why Windsor would seem to be an unlikely location for a successful large scale New Urbanist development. The local economy (along with many of the residents) is highly dependent on the automobile industry. Not only does this contribute to extreme variability in the local market, but it also predisposes Windsorites to a car culture. Public transit (buses) account for only three percent of trips and the private automobile is generally the mode of choice even when transit is available. In this setting, pedestrian oriented development is likely to have limited appeal. Local government, on several levels, has been reticent to fully embrace the New Urbanist concepts. The municipal government has, in response to market pressures, long fostered development regulations that are designed to facilitate the development of affordable home ownership opportunities. Alleys, sidewalks and other New Urbanist touchstones that add to housing development costs and to ongoing public maintenance costs have been eliminated or severely reduced in many of the other competing local developments. The implementation of the East Riverside Community Plan has received little support from local government operating agencies. The current political climate (in which inner city neighborhood schools face closure) makes it difficult to construct the new schools called for in the Plan. The public transit operator cannot provide extensive and frequent service to or within the East Riverside Community until economic standards can be met, with the result that the initial residents must rely on automobiles. The public works department has long opposed alleys for maintenance and cost reasons. The fire department wants wider streets for its equipment. The public utilities are reluctant to extend high maintenance "neo-traditional" items such as streetlights. Finally, the traffic engineers are skeptical of a restricted road hierarchy since the area does not fit into a surrounding pattern of grid streets. This skepticism is not limited to the public sector. The landowners who purchased the CN property generally had only limited interest in cutting edge planning innovations if their adoption meant slower sales. They are more concerned with obtaining a rapid and substantial return on their investment. While not necessarily opposed to the New Urbanist concepts of building place and community, they simply prefer developments that have the broadest market appeal. Much the same is true of the homebuilders. Residential developers in the Windsor market, many of whom are small-scale developers for whom a risk of slow sales may mean bankruptcy, have traditionally been extremely conservative. In general, this means that they are unwilling to innovate or offer features that will add unnecessarily to the cost to their products. Given the highly competitive nature of the local market for new housing in Windsor and its suburbs, East Riverside home builders are unwilling to add any features that will make their offerings more expensive and less competitive, simply to meet neo-traditional design standards. OUTCOMES AND LESSONS LEARNEDThe development of the East Riverside community is still in its early stages. Presently, there is an assortment of single-family homes, semi-detached and townhome units available. Only one non-residential structure has been approved. Even at this early stage of the development process, a number of trends are apparent, however. It is clear that the ultimate development of the East Riverside Community will be quite different from the ideal plan adopted in 1998. Among the most evident departures is the current separation of land uses, including different types of residential, lack of connectivity to the surrounding neighborhoods and the lack of variety in the development. Contrary to the desired notion of finely grained, highly mixed uses, individual builders are simply proceeding with their specific product on separate blocks. Pedestrian traffic is limited by the lack of available destinations and public transit is not yet available in the community. Some of these departures from the Plan may be resolved as the Community evolves and other components of the Plan are realized, and the critical mass necessary to support community services is achieved. Other important departures from the New Urbanist model will persist, however. The lack of alleys and the front loaded garages will remain, greatly compromising the quality of the public realm in the Core. The existing residential developments are contemporary in style, rather than traditional. As a result, much of East Riverside will be generally indistinguishable from other turn of the (Twentieth) Century suburban developments. It is clear that, as it has developed, East Riverside has failed to achieve many of the basic touchstones of New Urbanism. Although the original plan for East Riverside had impeccable New Urbanist credentials, in the course of implementation, the development has become at best a "hybrid". While some of the New Urbanist concepts remain, they are often seriously compromised. For example, the effect of the grid street pattern with residential structures placed close to the front property line is largely obviated by the front loaded garages. But despite these limitations, East Riverside has been a market success. The experience of failing to realize planning objectives while achieving market success provides a number of lessons. Perhaps the most important is that many of the key stakeholders in the development process, at least in Windsor, Ontario, were simply not ready to accept many of the more innovative aspects of New Urbanism. The landowners, builders and public officials remained skeptical that the more radical aspects of New Urbanism would be accepted. The local market reaction to the options provided certainly reinforced these beliefs. The fragmented land ownership contributed significant obstacles to the implementation. Many of the new owners lacked commitment or even interest in the realization of the original plan. The essential coordination of development timing (for example, ensuring that the neighborhood commercial was available concurrently with the early residential development) has proved impossible to achieve. If unified land ownership is not possible, then it is essential that all of the property owners share a commitment to the objectives of the plan. The need for commitment is not limited to the private sector. The multiple public agencies involved in the implementation must also share a commitment to the planning objectives. In the case of East Riverside, the Planning Department appears to be the only agency with a strong commitment to seeing the ideals of New Urbanism realized in East Riverside. Other public agencies, at best, supported the concept only so long as it did not require change in their existing policies. CONCLUSIONSAs proposed by the Toronto consultant the original plan for key stakeholders did not see the East Riverside Community as self evidently superior. Local public officials and the Windsor development community felt it was necessary to adapt the plan to the perceived realities of the Windsor market. The concessions and compromises that occurred in implementation have produced a development that falls far short of the New Urbanist ideal. The (entirely residential) development that has occurred thus far is uninspired but familiar. East Riverside today lacks a pedestrian oriented community core, one of the touchstones of New Urbanism’s emphasis on creating a sense of place. The East Riverside experience has provided local officials with a better understanding of what must be done to achieve the faithful implementation of an innovative plan. Key stakeholders must have a clear commitment (or at least a reasonable consensus) on the objectives that are to be achieved by the implementation of the plan. Flexibility in regulations and scheduling must be avoided if the prevailing market preferences are to be altered. Absent a firm commitment by the private sector to the realization of the comprehensive package of New Urbanist principles, it still might be possible to move closer to the ideal. In retrospect, the latitude provided in the zoning regulations, especially as they relate to single-family lot sizes, was too broad. Windsor’s zoning bylaw permitted lots only marginally narrower than those prevailing in competitive developments. It is not surprising that the homebuilders elected to provide a product as close as possible to that being offered by their competitors in other parts of the metropolitan area. Similarly, the absence of lot platting as part of the subdivision approval process did not result in a mix of housing types (singles, semis, townhomes) on the same block. Rather, the individual builders chose to build the type of units with which they were most comfortable, with the result that the residential areas offer only limited variety. One of the more disappointing aspects of East Riverside is the prominence of garages. The regulations did not prohibit garages in the front and the builders presumed that buyers would not accept detached garages at the rear of the lot. As a consequence, the front of virtually every unit is dominated by a garage, with little of the house visible. Front porches are virtually nonexistent. It seems clear that the development regulations must be much more specific in prohibiting (rather than simply attempting to restrict) front garages. Unfortunately, it seems likely that local development community has learned different lessons from East Riverside. They have been successful in selling homes that are as close as possible to homes they would have built in other subdivisions. Unless the currently unbuilt elements of East Riverside radically change the community, providing it with the desired sense of place and sense of community, we believe that the development community in Windsor will continue to see innovation and attempts to achieve better planning and design as obstacles rather than opportunities. Even if one considers East Riverside a modest success, it is unlikely to cause a paradigm shift in Windsor’s suburban development patterns. Given the nature of the Windsor market, there may not be another opportunity for a large scale New Urbanist development. The developable land within Windsor’s city limits is committed. Suburban municipalities, with vast amounts of vacant land continue to offer highly competitive alternatives in the form of more conventional housing styles. East Riverside may be the City’s last opportunity to achieve anything different.

Figure 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Apartments | Commercial | Business Park | |

| Maximum Density | 36 upa |

|

Maximum FAR 1.0 |

| Maximum Height | 12 stories | 4 stories | 1 story |

| Permitted uses | Residential | Commercial, Office, Residential | Light Industrial, large retail |

| Design Approval Required | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Copyright 2001 by Authors

Doug Caruso is the Director of Development Review Services with the City of Windsor (Ontario). In addition he is an Adjunct Professor in Planning at Wayne State University (Detroit) and the University of Windsor (Ontario). He is a member of both the Canadian Institute of Planners and the American Association of Certified Planners and was educated at the University of British Columbia (1968) and the University of Minnesota (1973). He is a past president of the Ontario Professional Planners Institute (Southwest Chapter), the recipient of an Outstanding Achievement Award (1997) and chair of Ontario Professional Planners 1997 Conference. He is the author of numerous articles and papers dealing with urban planning.

Gary Sands is an Associate Professor in the Graduate Urban Planning Program at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan and an Adjunct faculty member at the University of Windsor. He is a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners and has served on the Board of the Michigan Chapter of APA, most recently as Treasurer. Sands has a Master of Urban Planning degree from Wayne State and a doctorate in Housing and Public Policy from Cornell University. He has consulted extensively with public agencies, community based organizations and the private sector on housing policy and market research. Inquiries about this paper may be directed to him at gary.sands@wayne.edu.